Does home dupe us in the notions of its safety, in assuring us about our impulses for cradling, cocooning, burrowing into that which will never harm us, never turn against us, that which will fortify us against the outside world, serve as our fortress? Or does it really unfailingly protect us from all things harmful just because it's home?

Then why did Anne Frank’s home in Amsterdam and the homes of so many millions of other European Jews prove unsatisfactory as fortresses to protect against the raids, the intrusions, the unfathomable acts perpetrated by the Nazis? (I apologize that I'm invoking Anne Frank to those who think her story is overtold at the expense of others, but that story clearly demonstrates this concept I'm outlining, and since so many people know it, it demonstrates that concept in a way people can picture). Why then did Anne’s family’s home have to be carved out of an attic apartment in an office building, and why again did that presumed fortress ultimately fail? Why, not as in "What could have led to this?" because that we already know, but why, as in "What is it about home that cannot save us from the horrific, cannot fulfill the functions we expect it to?". Is it simply because we imbue the home with expectations it cannot actually meet? Or what? What's the point of a home (the typical meaning of home, the physical kind, on a city block or a plot of land), if it just means being ultimately defenseless? There are so many human rights abuses and social justice issues (forced relocation of towns and villages; gang warfare, which seems usually to rage close to the homes of the gang members themselves and close to the homes of others in their communities and neighborhoods; domestic violence, for instance) that pivot around the home, that reverberate outward from problems at home (even if defined in numerous ways) or from problems at the most basic levels, comparable to the basic nature of the home, those pesky basic needs of nutritious food, abundant water, decent shelter, and adequate clothing. I'd like to explore over time how these spaces, that we expect to be comfortable and harmonious, become otherwise and how they can come back to homeostasis, to equilibrium.

Switching gears here to a different degree of concerns about home as conflicted space, why is the physicality of the home itself also potentially the cause of our deaths? Or, why is the body so fragile? If our bodies are our homes at the most immediate level (perhaps the most immediate level is actually the cell, the genetic code, the atom, the subatomic particle), and we work outward, why do we suffer, and why can it all end with one stroke? Why do freak accidents happen all the time in the home? What's the point of a completely unsecure home, of utter fragility, of the constant threat of breakability? Again, what's the point of being ultimately defenseless?

Our bodies are no protection. We can choke at the breakfast table on a mouthful of Frosted Mini-Wheats. We can dash our hopes and dreams by becoming immobilized, we can fall down from almost any height and falling at a bad angle, paralyze ourselves. We can risk our lives by filling our homes with objects of utility that also pose harms, threats to our safety. Technology seems so helpful until you electrocute yourself, until it catches fire, until it explodes, until it poisons the air you breathe and otherwise poisons the integrity of your body, your organs, your hormones, or even your DNA.

Kitchenwares and other items made of delicate materials such as ceramic and glass seem ever so helpful until they shatter and imbed themselves in skin, or until they start to fall and we feel liable to protect them, salvage them, keep them from injury, and in attempting to keep intact that which refuses to remain intact, to cooperate, we leave ourselves open to great dangers, and the unwieldy objects drop anyway, and in dropping, slice apart our tendons, and nerves, and main arteries, potentially fatal activities starting with simple, trite objects, making the home much more a contested place than it otherwise, harmoniously, appears.

The latter of these countless unfortunate incidents and freak accidents, in which the home ceases to be shelter and works against us, occurred in my home two months ago today. I had just worked my last full day at one of the coolest bookstores in the world, having celebrated my going away with my co-workers and bosses. My boyfriend and I came home sometime around 6 o'clock. I went to go load the pictures of the party and of merchandise (to eventually add to the store's website) onto my computer. Peter brought me a glass of water and then, since we were supposed to be moving across the country at the end of that week, decided, especially since I'd been bugging him about it, to go wash dishes so that he could pack them up. Some time later I hear a loud crash in the next room and think that perhaps it's funny, all kinds of kitchen items toppling in a domino effect. We'd dropped many things in our kitchen before. But before I can assume this is true, I hear Peter screaming my name at the top of his lungs, over the sound of the water, through the barrier of the wall. I throw open the door, and there he is, wide-eyed and gripping his wrist as tightly as possible, a sanguine pool covering the kitchen tile.

Now I'm rushing across the living room, grabbing the phone, dialing 911, running over to his stereo and turning off the music he was blasting to entertain himself while performing monotonous tasks in the kitchen. And now the guy on the other end of the phone is telling me to wrap a clean towel around Peter's hand--and insinuating that this might not have been an accident. A little too early to add insult to injury, don't you think? We're rushing down the stairs of our apartment and waiting for a firetruck to arrive (they always send firetrucks to our neighborhood for emergencies). Peter tells me, "If I pass out, you're going to have to apply pressure to my wrist, or I'll die." Now that I'm beyond sufficiently panicked, the crew arrives, and Peter's talking with them about all sorts of things, the injury, his pain, having them drive me to the hospital, amazingly talkative for being on the verge of death.

At the hospital, though our family and a friend arrive, it's four hours of hell. Peter's joking every moment that the medical students and doctors aren't torturing him. They apparently don't know how to bandage wounds properly and unnecessarily hurt him as they wrap too tightly, unwrap, and rewrap the wound additional times because they can't tell how badly it's damaged. They're ready to go through this tortuous procedure time after time, without either giving him painkillers first or letting the drugs sink in, so we learn early on about the limitlessness of their cruelty. By this point, we'd already assumed (somewhat intuitively) that he'd cut his major artery and nerve and so would need surgery, long before they officially came to the same conclusion and decided on surgery.

He's in surgery for another four hours. Speaking of home, hospitals don't provide much of a home-like atmosphere for family members waiting for their loved ones to emerge from the operating room late at night. Eventually, the doctor comes in and tells us exactly what Peter cut (three quarters of the way through his major artery and median nerve, severing three tendons as well) and how exactly they reconstructed it all (opening the wound up to reveal a kind of triangle, zigzagging the cuts so that now Peter has a mark that makes everyone think of Zorro). When Peter does come bounding by in his hospital bed, we chase after him and his hurried nurse. He's loopy as hell from the drugs but still joking with his nurses. We run through the list of of Peter's medications (he's an amazingly unhealthy young guy) for the millionth time with the nurse, just as we had with the account of the injury (hospitals desperately need better methods of communication, of relaying information, than making the patient provide the same information several times). I stay with Peter while the family goes home for the night, we talk for a little while, and then I fall asleep in the stiff hospital chair. By the afternoon of the same day, we're taking Peter home to his parents' house, where he'll be comfortable, and I'm still dreading having to clean up the kitchen at our home. That night, after dinner with everyone, my friend and I drive to my apartment and attack the floor, the sink, the wall, and other stained areas with bleach. I try to do some other packing, to imagine sleeping the night in my own apartment, but all I can do is talk with my friends online about how shaken up I am. When Peter calls, we decide to have his dad come pick me up because I can't spend the night in my own house.

We set Peter up in occupational therapy to do flexor tendon exercises and delay our trip by about a week, and he starts to recover rather quickly, though one day he reacts strangely to the painkillers, yielding the perennially adorable groggy statement, "I love you...Cheesepuff!" (Cheespuff referring to his special, hospital-provided, bright-yellow foam arm rest). And by now, we've had a chance to talk over the whole ordeal, all the gruesome details. If nothing else, we most certainly know that the plate that broke in half and slid into his wrist just had it out for him. Still, the O.R. report comes back, stating, "He came in with a story of breaking a plate while washing dishes." A story, huh? No one trusts anyone anymore.

Ever since the evil plate enacted its vendetta against my boyfriend (of course the plate didn't actually have any agency; that's why we call it a freak accident--poetic license, thank you), I've been struggling with these notions about home as conflicted space. What meaning does home have on any level, as the code for our gene sequence, as our emotions, as our bodies, as our inhabited spaces, as our journeys, as our friendships, as our attachments, as our created communities, as our planet, if all of it is so fragile and destructible? Why bother creating when it can all be broken away? It's a very paranoiac view of the world, but as I'm still piecing through the trauma of that July night, I've got a lot of paranoia sitting on my shoulders. I don't like ceramic plates and other breakable items. I don't trust objects or very much of anything at all thanks to a very personalized Murphy's Law. How to counter these fearful notions about the home? How to create safety, or a sense of it, in the midst of a conflicted space?

Sunday, September 28, 2008

Home as Conflicted Space

Tuesday, September 16, 2008

The Permaculture Ethics of Landscape and Culture

(A final paper I originally wrote for my ethics class, December 2007.)

Ten thousand years ago, agricultural society sprang from the Fertile Crescent. Many thinkers (these include Marshall Sahlins, Jared Diamond, and Daniel Quinn) have argued in recent years that this was one of the most ridiculous pursuits in the history of the human species. I follow their logic, to such an extent that I have formed an understanding of humans essentially inextricable from their surroundings. We humans shape our surroundings but we are nothing if not malleable, and our surroundings influence our ways of living. Our landscape, the place we call home, and our culture are intertwined, and if our culture is based on the merciless destruction of that very landscape, our culture is based on a foundation that is already crumbling, and our culture will soon collapse, as well. If we place the focus not on the terrified response, “How do we save our presiding culture?” but on the question, “What basic tools do we need to move from collapse (of our culture) to a landscape (a place we can call home) that can sustain the presence of so many cultural refugees?” we will be much the better for it. I wish to offer the model of Permaculture in response to this question, with the added reassurance that we certainly have the tools available, we simply need to understand them better.

Care for the earth. Care for the people. Limiting of population and consumption. Further examination of these three principles makes it obvious that an overarching rule can be established, namely that, “The only ethical decision is to take responsibility for our own existence and that of our children. Make it now” (Mollison 1). These three principles combined, along with the overarching rule, form the whole of Permaculture ethics, a code established some twenty years ago by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren, two Australian horticulturists and designers seeking a better model for communities and a framework for sustainability. They established this model in Permaculture, a specialized design system that represents both permanent agriculture and permanent culture by incorporating all the edgiest practices of our time period—ecological landscape design, agro-forestry, sustainable agriculture, alternative energy, natural building, alternative economic models (usually localized economies), community building, and non-traditional education—into one field. Mollison and Holmgren grounded their new discipline of Permaculture in a simple code of ethics, which all Permaculture designers now share in common. But what makes these Permaculture ethics, well, ethical? I seek to defend in this essay, along with the conclusion that Permaculture can provide for the refugees of agricultural society where agriculture cannot, the ethical validity of the code of Permaculture ethics, especially as contextualized with other ethical theories and their principles.

Before exalting the merits of Permaculture, we should first consider individually each piece of the code of Permaculture ethics. If the only ethical decision to be made is to take responsibility for our existence and the existence of our children, why do we need the other three principles? Well, on its own, the directive, “take responsibility,” sounds awfully vague to me! Had Mollison and Holmgren stopped after writing down “the only ethical decision” they saw necessary for humans, they would have added nothing to the world in the way of solutions, much less environmental ones. Unless they wrote specific guidelines to sketch out what they meant by “take responsibility,” we might have the absurd case of people running around, monopolizing industrial agriculture, making millions of dollars a year while laying waste to the planet, saying they were taking responsibility for their futures and their children’s futures by securing assets to pay for their needs, and calling themselves “Permaculturists” on top of all that!

Lucky for us they did not do this, and now we understand responsibility to equate with care for the earth, care for the people, and limiting consumption and population. We might even find it advantageous to tack on a few more guidelines, an advantage which we will explore later. Care for the earth, an ethic defined as a “provision for all life systems to continue and multiply,” includes conservation of endangered plant and animal species, careful observation of natural processes, modeling the built human environment after any observed patterns we uncover in this way, and promoting polyculture over monoculture (Mollison 2). Care for the people, an ethic defined as a “provision for people to access those resources necessary to their existence,” manifests in ways such as eradicating the global slave trade, creating self-sufficiency in the community instead of providing the minimum charitable contribution, strengthening communication among individuals and groups so that anyone with new ideas will not be overlooked, and creating community-enriching attractions, such as museums, libraries, free schools, theatres, recreation areas, or restaurants stocked with local produce and goods (Mollison 2). Limiting population and consumption, an ethic that functions in such a way that “by governing our own needs, we can set resources aside to further the above principles,” comes into play in ways very distinct from the other two ethical guidelines (Mollison 2). It is realized in various instances, from education about fair trade to planning an alternative, un-materialistic holiday, such as a conscientious Christmas celebration, from the choice to live simply to an understanding of populations as a function of food supply. These ethical guidelines work together almost like fairy godmothers, illuminating the types of activity required in taking responsibility for one’s own future and that of one’s children.

The ethical code of Permaculture pertains to the contemporary ethical climate largely in an economical way. Supporting multi-national corporations such as Monsanto, which has a frightening monopoly on genetically modified crops, does not care for the earth, for seed and crop diversity, nor care for the people, for bankrupted small farmers defending themselves in court against Monsanto’s claims of unauthorized use of their patented seed, and doesn’t even limit population and consumption, for as much as Monsanto claims to have answers to nutrition problems across the world, there are healthier answers that do not involve ingesting as yet untested (on humans over time), brand new genetically modified foods, such as corn, tomatoes, soy beans, and potatoes, and that do not create further reliance on insupportable agricultural society. However, supporting a local independent bookstore, for example, can mitigate some of the damaging effects of our run-amuck society. Though local businesses cannot always offer the incredible sales or savings that online stores or big box stores do, they will, in a self-protecting way, invest money in other local businesses, so that each dollar spent there goes even farther in supporting the local economy. Also, local independent businesses have remained human-scale and are therefore less likely to treat customers simply as money-spenders but as unique people worth getting to know. In this way, they will respond to community needs and offer helpful services with ease and efficiency, without having to get approval from an almost endless chain of higher-ups. Most importantly, investing in our local economy overall helps make it our landscape, the place we call home, not just some landscape, some other being’s home.

If we buy all our produce, for example, from companies in California, we are laying waste to our own region. So much gasoline is wasted when items grown on industrial farms in Florida are trucked all the way to California and items grown on industrial farms in California trucked to Florida, big trucking ships passing in the night. It is a food system designed in a completely illogical manner, with industrial agriculture all over the place, even ruining our own region; even if the food we consume doesn’t directly come from the Midwest, something being produced in our region (in Nebraska and Iowa, that would mostly be the corn and soybeans to feed livestock across the country) inevitably has maintained in its essence the rest of the imbalanced structure. When we support small farms in our region, usually these farmers are thinking much farther into the future than those on the industrial farms, and so they are often turning to sustainable agriculture, providing options for Community Supported Agriculture (CSA’s), and forming into cooperatives (this is not confined to the more liberal coastal states, but is happening right here in the breadbasket of America).

Buying local is equivalent, then, not only to care for the people but care for the earth, as well. Local businesses are more likely to strive to improve the ecological health of their surroundings, their region, their landscape. But what about limiting population and consumption? By having to compete in an increasingly outsourced or globalized economy and by thinking of customers as people and not consumers who should “Buy, buy, buy!” local businesses take into consideration the limits of consumption that already exist, whereas the big businesses (which, it might help to point out, might have a headquarters in a place that would make them seem local, but they are not motivated by a devotion to their region) seem to think of growth as unlimited, even though this economic model is “an outmoded and discredited concept” (Mollison 1). Furthermore, “It is our lives which are being laid to waste. What is worse, it is our children’s world which is being destroyed. It is therefore our only possible decision to withhold all support for destructive systems, and to cease to invest our lives in our own annihilation…Most thinking people would agree that we have arrived at final and irrevocable decisions that will abolish or sustain life on this earth. We can either ignore the madness of uncontrolled industrial growth and defence [sic] spending that is in small bites, or large catastrophes, eroding life forms every day, or take the path to life and survival” (Mollison 1).

In almost every conceivable way, Permaculture offers an ethical solution to the ailments of the economic system of our deluded agricultural society that assumes it can run itself on the resources of the entire world at a rate of exponential growth, which is impossible if we wish not to devour ourselves.

Permaculture ethics have a useful framework to offer as an ecological matter, as well. In our consideration of the ethical benefit Permaculture design provides for ecological problems, we should tack on two additional ethical principles under our umbrella rule of “take responsibility.” These two new principles come from William McDonough and Michael Braungart’s book, Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things:1) “Once you understand the destruction taking place, unless you do something to change it, even if you never intended to cause such destruction, you become involved in a strategy of tragedy. You can continue to be engaged in that strategy of tragedy, or you can design and implement a strategy of change” (44).

With these five ethical guidelines in place (care for the earth, care for the people, limiting population and consumption, a strategy of change, and being 100 percent good), we can observe how these ethics would be ecologically valuable in a city like Omaha, a city that is plagued by its Superfund status from Asarco’s lead contamination. Care for the earth means healing the contamination by removing the lead, the contaminant, while care for the people means making everyone aware of the problem, providing resources to residents in the affected area, evaluating and treating poisoned children, and creating forest gardens, orchards, or community gardens in the treated areas to give the community a vision of hope and sustainability in place of the grim vision of pervasive contamination and ruin. Limiting population and consumption here can be viewed in its alternate phrasing, “Share the abundance,” which means once the contaminated area is healed and planted over with perennial goodness, all the members of the community may take part, sharing in the celebration.

2) “As long as humans are regarded as ‘bad,’ zero is a good goal. But to be less bad is to accept things as they are, to believe that poorly designed, dishonorable, destructive systems are the best humans can do. This is the ultimate failure of the ‘be less bad’ approach: a failure of the imagination. From our perspective, this is a depressing vision of our species’ role in the world.

“What about an entirely different model? What would it mean to be 100 percent good?” (67).

Thus, a strategy of change is the vehicle by which people decide that if poisoning the population didn’t work last year or the year before that and if it won’t work the next year or the year after that, then noticing this pattern and not doing anything about it is the strategy of tragedy and devising a wholly unique, relevant solution is the appropriate thing to do, in this instance, creating orchards and gardens for posterity, as an act of responsibility for the future that we, along with our descendants, will live in. Finally, the ecological applicability of the overarching ethic to “take responsibility” will follow the pattern of being 100 percent good, by not succumbing to the lie that the only thing we can do is curb our ridiculous behavior, to “reduce, reuse, recycle,” but rather by daring to think that we can craft an entirely different future based on good design, that will then prove to be 100 percent good to its very roots. In our Omaha example, this 100 percent goodness would take the form of re-conceptualizing our entire city model and framework and rearranging the elements of the city to work for ecological wellness instead of destruction, to eliminate the need for the “reduce, reuse, recycle” philosophy by eliminating waste from the functional structure of the city.

The other two ways in which Permaculture ethics are extremely useful are cultural and spiritual ways. In the groundbreaking work on child development, The Continuum Concept: In Search of Happiness Lost, Jean Leidloff explained much of our agricultural society’s psychological devastation as a function of child-rearing. In an interview, she explained the basis of her antidote: “The two words that I've arrived at to describe what we all need to feel about ourselves, children and adults, in order to perceive ourselves accurately, are worthy and welcome. If you don't feel worthy and welcome, you really won't know what to do with yourself. You won't know how to behave in a world of other people. You won't think you deserve to get what you need” (Mercogliano).

For me, this approach seems to combine easily with the rule, take responsibility for your existence and your children’s existence. It is much easier to take responsibility for our futures if we stop hitting ourselves over the heads and acknowledge our worth and the necessity for what we have to offer. We can then go out and follow the guidelines of Permaculture ethics from a place of stability, confidence, and ingenuity.

This cultural background is closely linked with a spiritual one. The spiritual stability I think is useful from the vantage point of Permaculture ethics comes from Daniel Quinn’s writings, in which he details the spiritual model of animism as an antidote to dominating and subjugating the earth to agriculture. When we acknowledge the benefits of viewing every element of our planet and everything on our planet as having a spirit, we can not easily maintain a relationship, based on domination, to all those spirits, to the coal and the Redwoods, to the buffalo and the Missouri, to trees or to people. In his collection of animist stories, entitled Tales of Adam, Quinn gifts us with Adam’s insight: “‘You’re wrong,’ Adam replied. ‘A certain kind of lion would do that, and I would track it down and kill it, because it’s a lion gone mad, a lion that kills whatever it sees, beyond need. It’s thinking: “If I kill everything I see, then the gods will have no power over me and will never be able to say, ‘Today it’s the lion’s turn to go hungry, today it’s the lion’s turn to starve, today it’s the lion’s turn to die.’ I’ll kill everything in the world so that I alone may live. I’ll eat the hare that would have been the fox’s, and the fox will die; I’ll eat the antelope that would have been the wolf’s and the wolf will die; but I will live. I shall decide who eats and who starves, who lives and who dies. In this way, I shall live forever and thwart the gods.” And this madness makes the lion into a murderer of all life’” (13-14).

This theme recurs in Quinn’s work, with the clear analogy running from lion to human (Quinn has written in The Story of B that “We are not humanity,” meaning the whole of humanity cannot be confused for the human victims of agricultural civilization, which he has dubbed Taker culture), the sort of human that lives in agricultural society. Agricultural societies carry with them an Ethos not apparent to anyone in the society, in the form of the concept that humans have the special privilege to decide who (or what) lives and who dies. Quinn’s character, Adam, makes it clear that this is not a workable Ethos. What Adam ultimately implies is that each individual should respect the Law of Life, defined as “how it was done from first to last, no two things alike in all the mighty universe, no single thing made with less care than any other thing throughout generations of species more numerous than the stars,” and not mistake herself for a god, for one who can decide who will die and who will live (Quinn 5-6). The directive of respecting the Law of Life and not intervening with life and death we can therefore append quite smoothly to the initial three ethics of the Permaculture code.

Finally, let us establish a seventh ethical principle in this ethical code. An argument for the essential quality of our evolving universe was put forth in the first of Jason Godesky’s Thirty Theses, a work interwoven with much of the philosophy of the environment I have discussed so far. He writes, “We can suppose another form of consequentialist ethics, like Mill’s Utilitarianism, but with a different measure of ‘good.’ It is not happiness, but diversity that should be our measure. Diversity of life, of thought, of action” (Godesky). The Principle of Utility becomes “The Greatest Diversity Principle” and replaces the old Utilitarian decision-making model. Bill Mollison’s emphasis on polyculture, Daniel Quinn’s emphasis on a multiplicity of tribes (instead of one monster culture, Taker culture), and McDonough and Braungart’s emphasis on a strategy of change, on good design and intentionality, all model themselves after the evolutionary advantage of diversity.

We see how Permaculture ethics match up to Utilitarian ethics, but what of other ethical theories? Certainly, Aristotelian ethics claim that humans have virtue when they flourish from functioning well. Those ethics hinge on the function of man as a rational being. What if we were to revise those ethics to hinge on the function of humankind as an ecological being, to relate to its landscapes in ways that support the ecological balance? That would certainly match up with the Permaculture ethics. Moral relativism flippantly discards any decision-making models other than those established by the individual, whereas Permaculture ethics, though it remains up to the individual to establish her definition of taking responsibility, has a set of guidelines to direct individuals on the ecologically-stable, moral path. Kantian ethics may be too inflexible to have much in common with Permaculture ethics, but one could argue for the directive to “take responsibility” that it is its own categorical imperative. Permaculture ethics are therefore not entirely unprecedented or incomprehensible; they even share certain elements with long-standing ethical theories.

We have seen that in these various contexts of economics, ecology, culture, and spirituality, as well as in the context of other ethical theories, the decision-making rule provided by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren holds true. So now we have one overlaying ethical directive, under which we have the following seven specific ethical principles or guidelines, all closely linked:

Overarching Ethic – The only ethical decision is to take responsibility for our own existence and that of our children’s, which existence is worthy and welcome.1. Care for the earth.

With these principles and this ethical code, our over-arching rule has a well-defined context. It becomes possible to apply, without being confused with agriculturalists, industrialists, and economists who see the whole world in terms of commodities that will provide unlimited economic growth, without consequences in the ecological fabric of our landscape, our home-place.

2. Care for the people.

3. Limiting of population and consumption (Also: Share the abundance).

4. Respect the Law of Life and do not mistake yourself for a god, for one who can decide who will die and who will live.

5. Design and implement a strategy of change if aware of current destruction.

6. Be 100 percent good if desperate for reversal of current processes.

7. The Greatest Diversity Principle: Maximize Diversity and Minimize Homogeneity OVERALL.

From the work of many visionaries and from the assorted examples presented

here, we start to shape an image of a culture on its last legs, faltering to keep its cultural Ethos hidden from all the humans in its grip (so that they can’t discover the irrationality and un-sustainability of its premise, that humans have the power to decide what should live and what should die). In our examination of Permaculture, we see an alternative, a horticulture-based culture that will be far from the evolutionary ideal but that could probably hold the weight of all the refugees of agricultural-based culture when it collapses. Through Permaculture, perhaps those of us participating in the culture that went so far astray ten thousand years ago can make the first few steps on the way to regrouping ourselves into the tribal configuration that has proven so workable for us throughout the history of our existence. We need only to take responsibility for our existence and that of our children.

Bibliography

Godesky, Jason. "Thesis #1: Diversity is the primary good.." The Anthropik Network. 19 July 2005. The Anthropik Network. 8 Dec 2007

Hemenway, Toby. "Is 'Sustainable Agriculture' an Oxymoron?." Toby Hemenway – Ecological Design and Permaculture. May 2006. 1 Dec 2007

McDonough, William, and Michael Braungart. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. 1st ed. New York: North Point Press, 2002.

Mercogliano, Chris. "An Interview with Jean Liedloff." An Interview with Jean Liedloff. Journal for Living. 1 Dec 2007

Mollison, Bill. Permaculture: A Designers' Manual. 2nd ed. Tyalgum, Australia: Tagari Publications, 1988.

Quinn, Daniel. Tales of Adam. Hanover, New Hampshire: Steerforth Press, 2005.

Keep reading: The Permaculture Ethics of Landscape and Culture...

Wednesday, September 10, 2008

On Blogging

I've created so many blogs, some of which have provided a nourishing framework in which to develop my ideas, yet they fall into all kinds of traps-- I post a couple times and then the blog just languishes, I don't keep a consistent focus, or I share too much about my life and then have to remove the blog from public display. Let's see if I can find some way to keep myself committed to this blog. I've obviously had an on and off relationship with blogging, but I find so much value in publishing my thoughts for anyone to read, without having to seek approval from a hierarchy of editors. One of the amazing things about intelligent blogs is that there's an inherent academic validity, or at least a genuine quality, without any kind of established standards or enforced rules. I imagine Wikipedia, for instance, would be more reliable if not for pranksters and incompetent writers with delusions of grandeur *. The open, uncontrolled format of the blog certainly allows for false information or carelessly presented information to appear on a respectably-designed blog, which can fool some people into thinking the information itself is respectable, accurate, erudite. I write later about the different forces pulling at the blog form, but for now, it is enough to say that the use of the blog by respectable people to share information quickly without interference by editors or censors is awe-inspiring and spectacular. As for my own blog, I'm glad to have a couple of models to follow, such as Anthropik and No Impact Man (which you can now visit from my revised links selection in the sidebar to the right of the page). Posts vary from academic responses to personal insights, with an occasional hodge podge of bullet points thrown in. I expect I'll fall into the same pattern.

I have had several initial ideas about the purpose of this blog. My first, broad goal was to get myself communicating with the world about my unconventional ideas about unknown subjects and undiscussed concerns. I wanted to move away from personal anecdote blogging to more scholarly writing about books I read, events I attend, and such. This purpose fused with a higher academic standard, an intention to weave together my interest in the not-so-well-known movement of primitivism with more well-known theory and mainstream philosophy. In conjunction with a seminar I am enrolled in at present, my personal blogging project of finally giving voice to my uncommon ideas has grown into a clear intent to share my work with my immediate academic community and to engage the larger community in this focused dialogue about primitivism and related issues. I guess I got too sick of constant self-criticism in the style of "If I am in the severe minority in my way of thinking about these things, perhaps I am wrong, or crazy, or just plain incompetent," and decided I would at least find out how remote my ideas were from those of others before I continued thinking in that vein.

These initial ideas developed over a long enough span of time that I reconsidered my wish to leave behind self-interested blogging for academic writing. I'm not sure any more that including some discussion of my subjective experience of the academic community is equivalent to self-indulgent writing. About that subjectivity...my personal and deeply emotional experience of the academic community and the alienation I feel there, not to mention my lack of a sense of belonging, which I actually have no problem with--let me make that clear, but it is such a strange, unique, awkward, and therefore, as I said, emotional experience that it seems I need to give voice to that experience, or even that it needs me to give voice to it, to name it in a community that disavows, dis-acknowledges it, even though the condition exists and has long existed, even though the problem persists. In my plans for this blog I, uncharacteristically, intended to be objective in some way, but I've never been able to accept objectivity as any kind of valid goal (I understand that many people practically worship the concept, especially for activities of high esteem, such as legal rulings or psychological experiments, but I have little patience with the idea that human beings have the capacity to exclude their own biases of any size from their deliberations and analyses) so I'm not sure why I didn't question myself on that sooner. Hence, my original purpose of separating the academic from the personal is a little naïve. Though I will try to keep my anecdotes and personal essays either brief or highly relevant, I have decided to pursue a very human approach to the academic topics I will grapple with in these electronic pages. I really am not naïve enough, as it seems many academics are, to presume that I can excise myself from the larger picture, the greater whole. That is the course I'm delineating for this project. If you object, please don't waste too much of your time trying to convince me I am wrong in my approach. Though I question the validity of some of my beliefs on the basis that I am the odd one out in relation to everybody else, I do not question my approach to expressing those beliefs and other thoughts. Kindly move along if you cannot reconcile yourself to my method of going about discussing these issues.

I briefly mentioned my blogging history above, but for the interested, I can detail it now, this being a post on blogging, after all. The uninterested may kindly skip ahead two to four paragraphs. In any case, my personal blogging story: Due to a server crash in early 2004, my first blog, named after my favorite band, died. The little community that constituted Kmorg (pronounced "Kay Morg") nurtured my fledgling blogging efforts and provided a comfortable space for a disgruntled high schooler to work through her ideas and disillusionment at the time. Kmorg was short for Killing Machines.Org; however odd that little detail might sound, especially when considering my interests and motivations, it was actually a very gentle, pleasant, and aesthetically-pleasing website, functioning as an independent weblog community with maybe 2,000 users. The same people then went on to host a similar project, HateLife, which promptly disintegrated for the same reason. Many Kmorg users like myself were disheartened that the inputs of time and money necessary to revive Kmorg were not available. The Kmorg operators were, however, kind enough to provide archives of the journal texts (no archives of the beautiful, picturesque sunset background, though) and recommendations of other blogging communities. They directed me to the blogging behemoths of the time, LiveJournal and Blogger (today, WordPress and TypePad enjoy similar popularity).

I chose Blogger for its simple design and devoted following. I figured a blog-hosting service with millions of users could manage its server issues, but I spent a little bit of time in late 2004 dabbling with LiveJournal because, for whatever reason, my friends preferred it. I spent much time with my primary Blogger blog during the 04-05 school year (which, incidentally, marked my first year of college), chronicling the eccentric behaviors of my friends and the notable experiences of that exciting first year, but when I returned home after having enjoyed one of my most valued life experiences in the summer of 2005, when I traveled to Brasil to learn about permaculture, I found I could neither convey what I wanted to about what I'd learned and experienced, nor could I keep up with the pace of my sophomore year in college and maintain a blog about my day-to-day experiences. After that, my blogs received much less attention from me for several years, with occasional posts and reorganization of my Blogger work space, but none of the intensive upkeep that I had maintained in my first year of blogging.

I now look back on much of my writing (as well as the writing of that Kmorg community as whole) from that time, that first dedicated year of blogging, as petty, but at the time blogging was a much-needed and much-appreciated outlet. Thanks to the retrospective view, I now understand the blight of blogging as a combination of the following: writing that is self-absorbed, hard to follow, illogical, unfocused, trite, too detailed/littered with inside jokes and references to have import for a wider community, unedited, and has no element of peer-editing (however informal, there is no connection to opposing views or bibliographic sources or a world beyond that specific blog), those kinds of things. As I do with many other elements of my life, I will fret about whether or not my writing fits my own criteria for decent share-able information, whether as a blog or as any kind of published material, but I view such fretting in a good light, in that perpetual consideration of the criteria, perpetual questioning can only make a piece of writing sharper, less unwieldy, more robust. If I learned nothing else from blogging over the years, I see how blogs serve different purposes and, accordingly, come in different kinds. The forum for a teenager's angst or venting is distinct from and incomparable to a critic's space for sharing reviews, stories, photos, excerpts, etc.. Yet both kinds, and many other special formats, are hosted on Blogger.

Though I would enjoy seeing a new standard and perhaps a separate space for blogging by intelligent people, if not people involved in Academia (say, an autodidact or unschooled high school student with insights galore), I do value the overall framework provided by blog-hosting websites for enhancing dialogue in general and for quickening the speed at which ideas can be shared. Though personal publishing may be so pervasive that it discredits the whole community participating in it, a discrediting that can occur by the mediocritizing force (the force that pushes accomplishments toward mediocrity) of overwhelming involvement by a mass in an activity, by the mainstreaming and overusing of a medium by all kinds of people, in which the uneducated, impolite, or irrelevant ideas of a few can mar the perception of all, it is kind of unfair. Personal publishing might be an eerily popular phenomenon, but how does that eeriness translate into a dismissal of decent work or intriguing works-in-progress on the grounds that the sharing of ideas by all kinds of people in all kinds of ways makes the medium entirely trite and worthless, without merit? That argument hits a little too close to elitism for me. Nothing else to say about my blogging history and outlook on blogging mediocracy (apparently that isn't a word, but I so wish it were, and spelled that way, too, that I'm going ahead and using it).

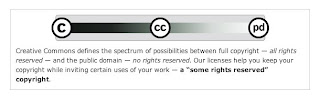

Since I am taking advantage of the phenomenon of personal publishing to share my thoughts with a wider audience, causing myself little to no hassle to publish my writing, I don't see why a little discussion of copyright wouldn't be useful, and so to begin...What force does a blog's implied copyright actually have? Posing that question more broadly, what kinds of values do copyrights perpetuate? I struggle with what kind of respect to give not only intellectual property laws but also the rationales behind them. Due to the increased access to information and self-publishing services spawned by the last century's increased connectivity, we are surrounded by ubiquitous soundbytes, ubiquitous memoirs, ubiquitous advertisements, bland photographs, unedited blog posts, unfinished webpages, illogical articles, unorganized nonfiction, boring fiction, pointless video clips, etc.. In that kind of unfiltered, information overload context, what worth does personal publishing online have, and what of copyrights? I have heard too many horror stories about the hundred year-old "Happy Birthday" song's creators extracting loyalties, of the hampered creative impulse of a writer who crafted a unique piece of fiction from the perspective of a character in another piece of fiction, in that case Gone With the Wind. Related horror stories about Monsanto's patenting of seed bring even more questions into view. The recent popularity of the Creative Commons license and open source code marks a tremendous shift in established modes of thinking about intellectual property. I find this shift in thinking very uplifting, in that there is new hope for breaking up the concentrated power of copyright-holders and breaking up the monotony of the stalemated discussion on changing intellectual property law. Whether or not lawmakers and officials were interested in letting copyright law evolve, the Creative Commons people took matters into their hands, as did other individuals and groups working toward similar aims. The Creative Commons' definition from their website:

This isn't my area of study (there are many more informed sources for an interested reader to explore), but it has always concerned me, so I thought it valuable to include some of my thoughts about copyright in a blog hosted on Blogger, which used to provide an informal copyright signature at the bottom of each blog. Because I've grown up with "all rights reserved" literature and legality, I'm accustomed to thinking about writers and creators as deserving of special attention, personal financial gain, and ongoing intake of loyalties. But in a collaborative world, where creative material will be shared one way or another and connections drawn among vastly different works in the constant unfolding of thought and creativity, the Creative Commons license of "some rights reserved" makes much more sense. If you wish to elaborate on my words or to connect my ideas to others I haven't considered, to share my writing with others or incorporate quotes from it into a paper, I will not hunt you down. Feel free to communicate with me about your own endeavors. If you do, I will not put a damper on discussion by requesting a donation or, worse yet, suing for such contribution. Let a Creative Commons-type copyright apply to my writing in this blog. I will consider applying for one as a formality, but you have now heard what I have to say on the topic.

I must also mention that Blogger's system of displaying posts doesn't exactly suit me. The reverse chronology is somewhat useful, in that any new posts are easily accessible to subscribers who have already read the whole of the blog. But what if certain posts would serve as better introductions to the blog than the newest ones? In order to keep my welcome post and other orienting information about my blog easily accessible, I've decided I will change the posting years for that handful of posts (because I have that strange time-traveling ability thanks to Blogger). I will include information about each post's truthful publication at the beginning of the post, and the displayed month and date at the bottom of each post will remain accurate, though even that reference point, that concept of accuracy, shifts, e.g. if the author adds content or edits pieces of the post at a later date. *Update, I've decided this is too much of a hassle and too strange. I will simply have the one post for guidance as an introduction to the blog, and I hope it is a a helpful post.

Another way I wish to modify Blogger's system of newest posts displayed first, with old posts obscured and drowned out by newer ones, is to provide one of those prioritized, welcoming posts I just mentioned, in which I direct readers to posts on different subjects. I'd like to set up something, perhaps series, that connects posts on related topics. I have few ideas for such series, such as one on design and another on home, or one on re-wilding and one on animism & ecumenism, but I'll have to postpone creating the introductory post for all the different series until I have some actual material to guide anyone toward. Actually, I am particularly excited to create a series of permaculture lessons (that I mentioned never having gotten around to after I returned from Brasil three years ago) so maybe these series will emerge faster than expected. Just a taste of all I have planned. Stay tuned!

As for comments, please take full responsibility for the content you post. Why waste your time masquerading as someone else or attacking anyone on insubstantial grounds if your post will simply get deleted with rapidity? Comments that contain excessive foul language, violent threats, personal attacks, or even intellectual attacks based on insufficient grounds, will receive this kind of prompt attention and be removed permanently from the discussion. The intention is simple-- to promote active, engaged, and relevant conversation about the issues at hand, issues too often ignored as it is. If a comment distracts from this purpose, then it will vanish from the thread, as I explained already. Thank you for you consideration.

* I apologize, my own prank. This kind of wiki article in this kind of hooligans' wiki database, however, captures very well what it seems has come to be called wiki vandalism. If such pranks could be completely relegated to Uncyclopedia, Wikipedia might actually succeed in making physical encyclopedia libraries obsolete, and as such, succeed in a small act of environmental activism to save all those tomes from being produced, hence saving acres upon acres of forest. However, the essential feature of Wikipedia, its open editing format, prevents such impropriety from going extinct. So long as Wikipedia remains true to its intent, pranksters will always blindside readers, in the process employing plenty of vigilant Wikipedia content-checkers for the entire existence of the database. And so, in the near future, people will still require unchanging articles from traditional encyclopedias to cite in their research.